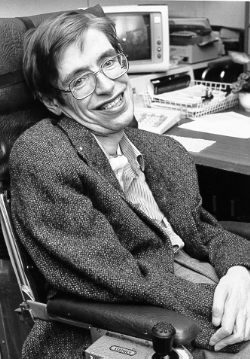

Stephen Hawking makes for an improbable celebrity. He hardly moves at all, and he tends not to make any noise. If you painted him silver, wheeled him to Covent Garden, and left an upturned hat in front of him, he would steal all the business from those people who pretend to be statues. Everybody associates Hawking with the machines that do the moving and talking for him. He controls the machines, but without them Hawking would be about as entertaining as a log of wood. In fact, without the machines Hawking would be significantly less entertaining than a log of wood, if you decided to stick the log on top of a splendid roaring fire. But that has not stopped Hawking from amassing an impressive list of film and television credits.

Stephen Hawking makes for an improbable celebrity. He hardly moves at all, and he tends not to make any noise. If you painted him silver, wheeled him to Covent Garden, and left an upturned hat in front of him, he would steal all the business from those people who pretend to be statues. Everybody associates Hawking with the machines that do the moving and talking for him. He controls the machines, but without them Hawking would be about as entertaining as a log of wood. In fact, without the machines Hawking would be significantly less entertaining than a log of wood, if you decided to stick the log on top of a splendid roaring fire. But that has not stopped Hawking from amassing an impressive list of film and television credits.

Why is Hawking a celebrity? His fame rests on two things. First, he wrote a very successful book designed to explain scientific ideas to a popular audience. Second, he has done some very smart maths about black holes. Nobody can dispute the number of books he has sold. But I can wonder if his cosmological maths is really any better than the cosmological maths being done by other brainy people. I do not not know about you, but my university maths education leaves me underpowered to form my own conclusions about Hawking’s abilities. I have to rely on the say-so of other bods as to whether he really is that clever. Take a look at this revelation that Hawking presented at a conference in 2004, and decide for yourself whether this makes Hawking smarter than the average cosmology professor…

The Euclidean path integral over all topologically trivial metrics can be done by time slicing and so is unitary when analytically continued to the Lorentzian. On the other hand, the path integral over all topologically non-trivial metrics is asymptotically independent of the initial state. Thus the total path integral is unitary and information is not lost in the formation and evaporation of black holes. The way the information gets out seems to be that a true event horizon never forms, just an apparent horizon.

I just about know enough maths to be familiar with the terminology in that statement, but I could not tell you what it means, whether it is true or not, or whether the conclusion could only be reached by a once-in-a-generation genius, or by any diligent Master’s student. I can, however, confidently state one thing about it. It has absolutely no practical use to anyone. Science or not, nobody is better off as a result of knowing this. To categorize it with trivia would be to do trivia a disservice. Knowing the answers to Trivial Pursuits questions like “which whale has a face like a dolphin?” (the beaked whale) and “which is the largest human artery? (aorta) might conceivably come in handy from time to time, and not just for the sake of winning Trivial Pursuits. But knowing that black holes do not form a true event horizon is of no use whatsoever (other than for the sake of winning Trivial Pursuits, if its makers ever include a relevant question).

Hawking has made many appearances as himself in shows that range from the most serious science fact to the very silliest science fiction. Despite that, as actors or narrators go, Hawking is not very good. The factors that make Hawking an ideal competitor at musical statues rather limits his abilities as a performer. This scene from Star Trek allowed Hawking to exhibit his full acting range.

Hawking has also done plenty of comedy over the years, and has even been prepared to do celebrity endorsements. Take a look at this advert.

Hawking the hawker – it is not a part he plays well. The mind boggles at the idea of Stephen Hawking zooming around in outer space in some futuristic spaceship, staring out of the window whilst flogging the centuries-old technology of spectacles. Perhaps Hawking also needs reminding that most of the galactic phenomena which are of interest to the mind also happen to be completely invisible to the eye. They were not kidding when they came up with the name black hole.

Apparently Richard Branson is determined to turn the Specsavers add into reality, by offering to launch Hawking into space. Obviously the deal is a perfect win-win for a celebrity scientist obsessed by space and a ceaseless salesman, who this time is trying to promote his fledgling space tourism business. It is currently unknown if smarty pants Hawking will point out the inconsistency between Branson’s plans to pack the super-rich into tiny tin cans sitting atop huge tanks of rocket fuel and some of his other headline-grabbing initiatives to protect the environment and conserve precious resources for future generations. Probably he will just take his seat on the spaceflight, stare out of the window, and keep schtum.

Hawking’s acting skills cannot win him new admirers. His maths equations are too complicated to understand and too irrelevant to our lives for anyone to care about them. That means Hawking’s major ongoing impact on society comes in the form of his musings on the nature of the universe. For this, he seems to be revered by many. My university education in mathematics may not have been enough to check his sums, but my university philosophy education is more than enough to tell me that when Hawking talks a lot of philosophical codswallop. Take a look at this clip, where he talks around a few ideas from various thinkers.

There are lots of shortcomings in Hawking’s worldview. One of those is that he assumes a positivist framework. Without getting into the detail, positivism ultimately seeks to base all knowledge on sensory experience. Yet Hawking, by virtue of the work he does, must rely on extreme extrapolations from the minute amounts of indirect evidence he has to work with. Theory gets built on theory, built on more theory, built on more theory… and only after a lot more theory do you finally arrive at something that you and I can see or hear. When Hawking talks about event horizons, it is not like he double-checked his results by jumping into a spaceship and going to look at a black hole up close. So what makes Hawking popular – giving answers to questions that have a deep emotional significance for many people – can only be justified on a very tenuous and contingent basis. If Branson ever tried to sign a contract with Hawking, with a view to placing commercial reliance upon Hawking’s theories, the caveats would stretch from this end of the universe to this end of the universe, having completed an orbit of the universe in the meantime.

Hawking also takes liberties with other thinkers, when trying to popularize his ideas and compress other ideas to fit his way of thinking. For example, in the above clip, what Hawking says about Immanuel Kant is wrong. I cannot go into the detail now (it would probably take a 10,000 word thesis to do the topic justice, and I doubt any of you would read to the end) but Kant’s understanding of time was far more subtle than the gross oversimplification presented by Hawking. Kant was a bone fide genius, who changed the intellectual universe in his lifetime and for centuries afterwards. Without Kant, the world would be a very different place. To give a couple of examples, both Marxism and German jurisprudence have an intellectual lineage which can be traced back to Kant. In contrast, it seems unlikely that Hawking’s research will have a lasting impact on the lives of many people. Contrary to what Hawking states, what Kant wrote about time was not just some superficial analysis based on then dominant and mistaken assumptions of physics, but a deep and sophisticated reflection on how we, as humans, comprehend the universe and hence are actively engaged in determining it. Kant’s ideas about time, like his ideas on many other topics, were fresh and revolutionary. In contrast, Hawking’s dismal dismissal of Kant is nothing less than a pop philosophy travesty. But then, you can hardly expect Hawking or anyone else to sum up some of the most intricate and imaginative reasoning of a genius in a couple of slides – just like two Powerpoint slides would not be enough to explain Hawking’s work on black holes.

Maybe Stephen Hawking is a brilliant mathematician, but not that smart or deep a thinker. That does not make him a bad person. Popularizing science is a very good thing for which he deserves a lot of credit. But some of Hawking’s output has turned the noblest of man’s intellectual adventures into lazy popcorn entertainment – to be digested passively without really encouraging thoughtful engagement with the ideas presented. It may leave the audience feeling inspired, but does not challenge them to think. And that should be a damning thing to say about a man of science.

The following clip gives us a lovely insight into Stephen Hawking, and some unexpected evidence about his nature. If comedian Jimmy Carr is telling the truth, it rather suggests Hawking is a very very nice man, but not very smart at all…

The fame of Stephen Hawking appears to be one of those self-perpetuating cycles of celebrity that emerge from time to time, like Jade Goody or Carol Vorderman. A door is opened to new opportunities, and each opportunity leads to another, like a chain reaction. Once the cycle is instigated, there is no proportionate connection between fame and merit. The most recognizable thing about Stephen Hawking is his voice, but it is not his voice at all. It defines Hawking in the imagination, and his pop culture appearances all draw heavily on the distinct tones of his voice simulator, which turns out to be NeoSpeech’s VoiceText product. Quite often we only hear Hawking, and do not see him. He may be narrating, or lending his voice to an animated caricature of himself. After all, unlike actors that run, Hawking is unlikely to do things that are visually stimulating. So when Hawking gets the credit for his voice, why is the credit not going to NeoSpeech instead? They are the ones who really made the sounds, and there will be many times where Hawking is just working from a script written by someone else. Think of the scenario: you give Hawking his lines, and get him to laboriously blink and blink again until he has programmed his machine to recite the words. I presume you record him from his home location, by setting up the microphone where he is, rather than flying him to some recording studio in Hollywood. But given the obsession with CGI simulation in so much modern entertainment, why take the trouble to be authentic and make Hawking do all that blinking and winking that he does to run his computer, when the makers of a show could just as well get their own version of the software and cut out the middle man. In fact, they could save themselves the trouble of paying Hawking too, though they would need to replicate Hawking’s customization of the speed and pitch of the voice.

If there was an innovation, and there was a way to give Hawking back his voice, and make him sound just like Anthony Hopkins or Richard Burton, would Hawking lose some of his fame? Perhaps. We live in a topsy-turvy world where people seek knowledge and inspiration from someone who does obscure mathematics about objects that are incomprehensibly far away. We live in a world constantly changing and expanding because of new ideas, from medical discoveries to computing breakthroughs, yet the poster boy of science is a man who draws the false conclusion that insight into the mathematics of cosmology is the same as insight into the world we experience. It befits Hawking that an enabling technology is both part of his fame, and a reminder that even science has limits.

So instead of going into detail you use an authority argument for why Kant was right about time. I do know how Kant explained space an time as fundamental categories that allow us to know things about our world. But I agree with Hawkin that the Kant’s example of finite vs infinite time to show metaphysics lead to contradictions has not been the best example to show this. I think the theory of relativity shows that the nature of time has come into the realm of phenomena, and therefore we can Know things about it.