When it came to religion and politics, the beliefs of British SF writer Iain M. Banks were never subject to doubt. Whilst dystopian futures feature in some of the best SF, and are also found in much of the worst of the genre, comparatively few writers set their stories in a triumphant, confident utopia which they unashamedly adore. Even fewer attempt to repeatedly wring dramatic stories from such an unpromising setting. Perfection does not lend itself to tension. Hence Banks tends to construct scenarios where his beloved Culture, a galactic post-scarcity civilization, has to lower itself to dealing with barbarians at its borders. The clash of civilizations gives Banks ample opportunity to express his views on religion and politics, by comparing the examples which he favors with those he deplores. With that in mind, I want to consider a particular question: might we say that Iain Banks’s Culture manifests a certain spirituality, or a ‘tao’ which goes beyond crude materialism? And if so, is this tao uplifting?

Banks’ disdain for any alternatives to his utopia are made plain. Barbarians might have religion; the Culture has long abandoned superstition. Different genders of barbarian species may adopt differing roles within society; citizens of the Culture do not experience gender except as another aspect of physical pleasure, and they change their gender at will. Barbarian societies might have governments, hierarchies, even businesses, whilst the Culture has no need for them… though close inspection suggests this conclusion is false. In short, the Culture is an atheist communist interstellar paradise, the kind of society that Marx might have dreamed about, if he dared to imagine the workers had achieved class consciousness, then invented benevolent machines that made them all redundant. Banks’ Culture is pristine, unsoiled by any of the messy internal compromises that real communist societies have felt necessary to accept, irrespective of the pressures created by external rivals. However, the behavior of real communists has sometimes been compared to that of religious zealots; as Karl Popper observed, Marxism tends toward a pseudoscientific worldview, demanding a degree of faith not supported by empirical observation. Because we can analyze the values of a political dogma as if it were a religion, we can make sense of the question I posed above.

To begin with, let us characterize what the Culture is, distinguishing what is described in the novels from some of the labels that Banks and others have wanted to apply to it. It is a civilization whose technology has conquered scarcity and has no higher purpose than gifting its citizens long, indolent and indulgent lives, whilst assimilating other civilizations as rapidly as it can. There is no capital, no money of any description, and no private enterprise, except in the sense that private individuals may do as they please. The society is hence communist, though perhaps communism does not really apply as there are no longer any workers to own the means of production. Private property seems to persist – for instance, people appear to treat their homes and clothes and pets as if they are belongings – but everybody can have what they want simply by asking for it. Strangely, nobody ever wants a unique possession that is already owned by another, such as an historic relic, or somebody else’s goldfish, or the product of a foreign economy. Furthermore, nobody has appetites so great that they would test the limits of what the Culture could supply. As such, the limits of the Culture’s liberal anti-capitalism remain conveniently untested.

At the same time as giving every citizen so much material freedom that they never desire more, the economy of the Culture is subject to centralized planning. The planners of this society are Minds, artificial intelligences of such scale and subtlety that human beings would be unable to determine if they were manipulated by them. Fortunately, what the Minds want coincides with what everyone else wants, although Minds are seemingly capable of disagreeing with each other. So whilst Banks and others have a desperate desire to label the Culture as anarchist, its citizens are free in the same sense that animals in a nature reserve are free; they lack both the mental capacity and desire to explore the limits of their freedom, though at some level they are governed by intelligences beyond their comprehension. In short, Banks and others make the mistake of confusing the wildness of the animals with whether the reserve is governed.

In another paradoxical twist, all ‘work’ is done by non-sentient machines, but both humans and intelligent drones choose to occupy roles that we would describe as jobs… although none of them demand payment in return. Admittedly, these jobs always seem to be inherently desirable, not least because of the status they confer. The Culture has plenty of architects, poets, diplomats and spies, but has no plumbers or waitresses, and it is unclear if anybody thinks childcare is vocation. A disproportionate number of the Culture’s citizens work in academia, being professors of almost any subject except the ones where the vastly intelligent Minds would clearly know all the answers already. Nobody needs to clean the toilet or process garbage, because dumb machines do all that. Even more oddly, there are intelligent drones which supposedly possess all the same freedoms as any human being, but who want to perform the tasks they have been designed to do. In other words, the Culture is an anarchy only in the perverse sense of the word that communists often employ: everything important is planned and ordered from the top down, but its subjects have been educated and improved to such an extent that the vestiges of their selfish desires always fit harmoniously within the designs of the elite who make all the decisions.

I could keep picking away at Banks’ description of the Culture, but that would be niggardly. Weaving a world on such a scale will always result in some loose strands and frayed edges. It is enough to say the Culture is a kind of communist atheist society that a modern Western social liberal might applaud. Its citizens are free to do the kinds of things that many of us dream of doing, enjoying plenty of casual sex and aimless recreation, whilst never suffering pain or hardship. On the other hand, the Culture’s citizens have evolved to the point where they never choose to do any of the other things that people currently enjoy doing, but which are anathema to modern Western social liberals. This includes: praying, raping, farting, stealing, being faithful to a partner or jealous of their infidelities, telling a rude joke to somebody who does not want to hear it, or asking for your bit of economy to be exempt from somebody else’s ‘planning’. Banks presents a society whose perfect values leads every citizen to be similarly perfect… or at least free of the vices and flaws that human beings have exhibited throughout recorded history.

As a consequence of being so perfect, there is a division of the Culture called Contact, which sequesters huge amounts of resources in a rather secretive and corporatist manner, and uses them to civilize every other society it encounters. This being a socially liberal utopia, any comparisons to empire-builders or missionaries are deeply unwelcome, even if they seem apt. I treat this as a crucial hint of the quasi-religious faith that underpins the Culture. The Culture’s mission includes expansion, but questioning the need to expand is somewhat taboo. Though it has the technological and material superiority to defend itself from aggressors, the Culture does not merely seek to preserve its borders, and to serve those who already lie within. The Culture also seeks to spread and assimilate, sharing the benefits of its wisdom even with societies that are deeply hostile to it. This extravagant self-confidence is not enough to demonstrate a tao that goes beyond the base cause-and-effect of materialism, but it might be evidence of a tao.

Like some philosophical arguments for the existence of God, Banks might think the Culture cannot be perfect without also seeking to maximize the reach of its perfection. And so, if there is a perfecting force within the universe, it necessitates both the existence of the Culture, and that the Culture spreads until it is ubiquitous. The Culture expands its borders because it is vital; the extension of its range may be the consequence of its tao.

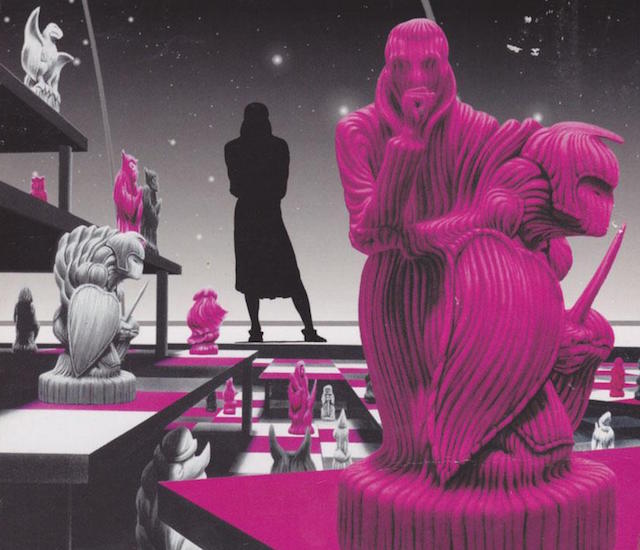

With so many Culture novels to choose from, I fear an exhaustive examination of them all would leave the Culture’s tao as ineffable and superficially paradoxical as the Tao described by this planet’s Taoists. For that reason, let me look for more evidence of the Culture’s tao within the confines of a single novel. The Player of Games was the second Culture novel to be published, and it was reworked from a draft that Banks had written many years before. As such, there is a good argument for saying this novel should represent the spirit of the Culture as Banks envisaged it.

The story was written early enough to capture Banks’ original thinking on the Culture, but being the second published novel it can explore concepts that are essential to the Culture without needing to be so hesitant about the audience’s sympathies. The story is about an interaction between the Culture and another civilization with contrary values, focusing on a single citizen of the Culture, the game-player Gurgeh. He visits the barbarian civilization of Azad, which takes its name from the extraordinarily complicated game that is used to select its ruler. Gurgeh enters the tournament whose winner is appointed Emperor, ostensibly playing as an honorary guest-cum-diplomat, though the underlying goal is to destabilize the Azad government.

The heart of this story is about communication. Whilst the game-players are competing for victory, their moves are also a form of expression. The complexity of the game means this expression may be as sophisticated, comprehensive and nuanced as that which may be conveyed through language or art. In an important and fundamental sense, the game can be a vehicle for different cultures to talk to each other. This leads to a telling question which will help us examine the Culture’s tao: what does the game-playing style of Gurgeh say about the Culture?

Before answering that question, it is necessary to assess if Gurgeh is speaking for the Culture, or merely for himself. Gurgeh is not a philosophical man, having spent his entire life perfecting his skill at playing many different kinds of game, most of which concern the movement of pieces upon boards, or the shuffling of decks of cards. Outwardly this superficial life is perfectly suited to the endless recreation of the Culture, and Gurgeh enjoys the adulation that comes with his many victories, but he may not be truly representative of the Culture. In fact, the story begins with Gurgeh feeling a sense of ennui; as comfortable as his life his, he is not happy unless he wins games, and whilst he is a peerless game-player, even the joy of victory seems to be wearing off. On the second page of the novel, Gurgeh asks himself: “what am I doing here?” having been drawn into a recreational activity which is typical of the Culture but which Gurgeh finds silly and pointless. He challenges his love interest, Yay, who persuaded him to take part:

It’s infantile, Yay. Why fritter your time away with this nonsense?

This is a confrontational question, given that every inhabitant of the Culture spends their whole life fritting away time on activities which mean nothing. However, Gurgeh also admits that he bores easily. As such, the reader knows that Gurgeh is not fully at ease with himself or others. When questioned why he lives alone, Gurgeh tells his friend Chamlis:

“Nobody can stand to live with me for long.”

“He means,” Chamlis said, “that [Gurgeh] couldn’t stand to live for long with anybody.”

Gurgeh’s lifestyle is depicted as idyllic, with a beautiful home, many admirers, and easy access to sexual partners. However, he admits:

“Everything seems… grey at the moment, Chamlis. Sometimes I start to think I’m repeating myself, that even new games are just old ones in disguise, and that nothing’s worth playing for anyway.”

If Banks intends Gurgeh to be the ‘voice’ of the Culture, as selected by the Minds that govern it, he also allows Gurgeh to question the superficiality of its ideals. Part of the problem with the Culture is an absence of meaning that can only be the result of taking risks:

“I used to think that context didn’t matter; a good game was a good game and there was a purity about manipulating the rules that translated perfectly from society to society… but now I wonder.”

He nodded at the board in front of him. “This is foreign. Some backwater planet discovered just a few decades ago. They play this there and they bet on it; they make it important. But what do we have to bet with?”

Gurgeh’s friend Chamlis agrees that Gurgeh is not perfectly adjusted to the Culture:

“You are a throwback,” Chamlis told him. “The game’s the thing. That’s the conventional wisdom, isn’t it? The fun is what matters, not the victory. To glory in the defeat of another, to need that purchased pride, is to show you are incomplete and inadequate to start with.”

Gurgeh then pinpoints why he feels ill at ease:

“This is not a heroic age… The individual is obsolete. That’s why life is so comfortable for us all. We don’t matter, so we’re safe. No one person can have any real effect any more.”

At this point, I think it worth noting how Banks has invested so much creative energy into describing a utopia which he clearly agrees with, but Banks is still willing to beautifully articulate the feelings of a character who is dissatisfied with life in that utopia. Banks deserves credit for this. It also suggests Banks would not be satisfied with a utopia that is completely inert. Gurgeh’s call for heroism gives us a hint that the Culture should be a moral force, capable of exerting a dynamic influence as well as coddling its inhabitants.

Chamlis responds to Gurgeh by mentioning Contact, the division of the Culture which does take risks and engage dynamically with forces it cannot perfectly control.

“Contact uses individuals,” Chamlis pointed out. “It puts people into younger societies who have a dramatic and decisive effect on the fates of entire meta-civilisations.

However, Gurgeh is dismissive of Contact, saying the people who work for Contact are “selected and used,” and comparing them to “game-pieces”. As he such, he illustrates how the ‘anarchism’ of the Culture culminates with a hard-headed elite who seek not just to govern within the Culture, but also to govern those outside it. When pressed on the subject of whether Contact could help him tackle his ennui, Gurgeh says:

“I have no intention of applying to join Contact… Being cooped up in a GCU [a very large spacecraft] with a bunch of gung-ho do-gooders searching for barbarians to teach is not my idea of either enjoyment or fulfilment.”

Gurgeh’s failure to fully embrace the Culture’s values is also emphasized in other ways:

“I feel you want to… take me,” Yay said, “like a piece, like an area. To be had, to be… possessed.” Suddenly she looked very puzzled. “There’s something very… I don’t know; primitive, perhaps, about you, Gurgeh. You’ve never changed sex, have you?” He shook his head. “Or slept with a man?” Another shake. “I thought so,” Yay said. “You’re strange, Gurgeh.”

Being a little unsettled and anti-social compared to others, Gurgeh is unusually sympathetic to Mawhrin-Skel, an intelligent drone which is a dangerous misfit by the Culture’s standards.

The little drone annoyed and amused him in almost equal parts. It was rude, insulting and frequently infuriating, but it made such a refreshing change from the awful politeness of most people.

Mawhrin-Skel’s discontent with the Culture is more noxious than Gurgeh’s:

“Oh, it’s all so wonderful in the Culture, isn’t it, Gurgeh; nobody starves and nobody dies of disease or natural disasters and nobody and nothing’s exploited, but there’s still luck and heartache and joy, and there’s still chance and advantage and disadvantage.”

Mawhrin-Skel has been ostracized from Contact, ostensibly for being too aggressive, even though the drone was designed to engage in combat. As a consequence, its talons have been removed, with the extraction of much of the military hardware it previously incorporated. In describing the original purpose of its life, Mawhrin-Skel chooses words which have biblical overtones:

“… imagine what I feel, all set up to be the good soldier fighting for all we hold dear, to seek out and smite the barbarians around us! Gone, Jernau Gurgeh; razed; gone.”

Gurgeh’s boredom leads him to cheat at a game with the encouragement and assistance of Mawhrin-Skel. However, the duplicitous and belligerent drone had manipulated Gurgeh with the intention of blackmailing him. It knows Contact wants Gurgeh to volunteer for a particular mission, so pressures Gurgeh to take the mission and use his influence to have Mawhrin-Skel reinstated. When Gurgeh learns the mission will involve traveling to Azad, a civilization outside of the Culture, he rationalizes:

…Gurgeh never ceased to be fascinated by the way a society’s games revealed so much about its ethos, its philosophy, its very soul. Besides, barbarian societies had always intrigued him, even before their games had.

And when Gurgeh contemplates what it would be like to travel outside the Culture for the first time ever, he looks at what life is like inside the Culture:

Something about the square, the whole village, disgusted and angered him. Yay was right; it was all too safe and twee and ordinary.

Gurgeh is briefed about his mission. The briefing further confirms how the Culture views other societies, as well as explaining why Contact needs Gurgeh’s assistance.

“Every now and again, however, Contact disturbs some particular ball of rock and discovers something nasty underneath. On every occasion, there is a specific and singular reason, some special circumstance which allows the general rule to go by the board. In the case of the conglomerate you see before you – apart from the obvious factors, such as the fact that we didn’t get out there until fairly recently, and the lack of another powerful influence in the Lesser Cloud – that special circumstance is a game.”

The society of Azad is described, with great emphasis on its faults compared to the utopian nature of the Culture.

“Empires are synonymous with centralised – if occasionally schismatised – hierarchical power structures in which influence is restricted to an economically privileged class retaining its advantages through – usually – a judicious use of oppression and skilled manipulation of both the society’s information dissemination systems and its lesser – as a rule nominally independent – power systems. In short, it’s all about dominance. The intermediate – or apex – sex you see standing in the middle there controls the society and the empire. Generally, the males are used as soldiers and the females as possessions. Of course, it’s a little more complicated than that, but you get the idea?”

Per the geniuses that run the Culture, a society like this would normally have crumbled long before it reached its current range and technological sophistication. However, the ruling game of Azad is the factor that has held it together.

“… Azad is so complex, so subtle, so flexible and so demanding that it is as precise and comprehensive a model of life as it is possible to construct. Whoever succeeds at the game succeeds in life; the same qualities are required in each to ensure dominance.”

However, the astute reader will have noticed that the hierarchical Azadian society is being described dismissively by an agent of the Culture’s hierarchical Contact division. Though Contact has not been elected by the public to influence or control other societies, that is how they see their purpose. Mawhrin-Skel perceived its role as essentially defensive, but Contact is actively engaged in coercing societies which pose no serious military threat. And when considering how the Azadian hierarchy controls information, there is another comparison that Banks seems blind to:

“If we let everybody know about Azad we may be pressured into making a decision just by the weight of public opinion… what may not sound like a bad thing, but might prove disastrous.”

“For whom?” Gurgeh said sceptically.

“The people of the empire, and the Culture. We might be forced into a high-profile intervention against the Empire; it would hardly be a war as such because we’re way ahead of them technologically, but we’d have to become an occupying force to control them, and that would mean a huge drain on our resources as well as morale; in the end such an adventure would almost certainly be seen as a mistake, no matter the popular enthusiasm for it at the time. The people of the empire would lose by uniting against us instead of the corrupt regime which controls them, so putting the clock back a century or two, and the Culture would lose by emulating those we despise; invaders, occupiers, hegemonists.”

This passage is dripping with irony, though Banks appears not to be conscious of it. The only reason this peace-loving ultra-transparent anarchy has not already invaded Azad is because an unelected elite has withheld information from the public! Instead of entering into direct confrontation, Contact intends to promote change in Azad by destabilizing its government. Does it not occur to anyone in the Culture that there is another option: to leave the Azadians alone? Whilst I feel this passage illustrates a flaw in Banks’ crushingly utopian morality, it also serves as an unflinching statement of its moral purpose. To be of the Culture, and to think like the Culture, means seeing yourself as anarchist liberators of oppressed people, willing to compromise every anarchist principle in order to achieve that goal. And the goal of liberation overrides the wishes expressed by the people being liberated; they must be liberated by the Culture, even if they neither seek nor want the Culture’s interference. This is not my tao, but it is a tao.

Fortunately, Banks saves himself from all the liberal paradoxes of his position by doing what communists often do: justifying the need to save the people by demonizing those same people.

“They have done things the average Culture person would find… unspeakable. A programme of eugenic manipulation has lowered the average male and female intelligence; selective birth-control sterilisation, area starvation, mass deportation and racially-based taxation system produced the equivalent of genocide, with the result that almost everybody on the planet is the same colour and build. Their treatment of alien captives, their societies and works is equally…”

There is no need to keep on quoting. In fact, the middle third of the book is devoted to one long laundry list of how utterly despicable Azad is. Poverty, theft, prostitution, sexual perversion, drugs, torture, corruption, hypocrisy, murder, inequality, deceit, sexism, cruelty to animals, jaywalking and nose-picking… Azad suffers from every vice imaginable. Azad’s prevailing ideology is Nazism on steroids.

Banks’ garish depiction of Azadian society serves as a wonderful distraction from the essential question that liberals should ask themselves: “as horrific as we find their society, why is it an obligation to overturn their way of life and impose our own?” Though not answered, this question is vital to understanding the tao of the Culture. The driving logic of the Culture, as epitomized by the behavior of its Contact division, is that of a false dichotomy that always leads to the same conclusion. If they encounter a society that is like the Culture, they will not disrupt it, and assimilation is inevitable. On the other hand, if they encounter a society unlike the Culture, then it is morally necessary to disrupt/educate/civilize (delete according to taste) that society until it is ready to join the Culture. In terms of the progressive march of history, this worldview could almost have been copied straight from a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary manual.

Whether intentionally or not, Banks shows that petty policing of language is used to disguise the arrogance of the Culture.

“They do,” Gurgeh said, “sound fairly…” – he’d been going to say ‘barbaric’, but that didn’t seem strong enough – “… animalistic.”

“…Be careful, now; that is how they term the species they subjugate; animals. Of course they are animals, just as you are, just as I am a machine. But they are fully conscious, and they have a society at least as complicated as our own; more so, in some ways. It is pure chance that we’ve met them when their civilisation looks primitive to us; one less ice age on [their homeworld] and it could conceivably have been the other way round.”

It is necessary that the Culture destroys/reforms/saves the horrible horrible Azadians whilst avoiding the use of pejorative language to describe them! And why are they in the position to do this? By virtue of ‘pure chance’! This passage implies an absence of morality: might is right, and the Culture just happens to be much mightier than the Azadians. However, the subsequent development of the story contradicts the bleakness of this especially amoral quote.

Gurgeh is persuaded of the need to compete in the Azadian tournament, and so undermine its government. I do not like the moral logic that Banks deploys, which relies on cheap stunts (genocide, racial extermination!) to gloss over the fact that the Culture has a central plan that involves assimilating every society, no matter how similar or dissimilar it is to theirs. But there is a moral logic here, and the conclusion is always: they must assimilate other societies for the good of the people living in them. Is this sufficient to demonstrate that the Culture has a tao? Probably not. The argument for the Culture’s tao comes at the end of the story, when game-player Gurgeh has reached the peak of his abilities at a game that is “so complex, so subtle, so flexible and so demanding that it is as precise and comprehensive a model of life as it is possible to construct.”

The journey to Azad takes years, and during that time Gurgeh studies the rules of the incomprehensibly complicated game he has been sent to play. Banks had set up his central character to feel vaguely dissatisfied with the Culture, so when Gurgeh finally arrives in Azad, Banks slaps him hard in the face. The author presents both Gurgeh and his readers with all the shocking reasons they should be grateful to live a ‘twee’ life that is the product of benevolent central planning. Gurgeh’s adventures all confirm the monotonously awful nature of Azad’s society. Meanwhile, the game-player improves his skills whilst winning match after match, despite the strenuous efforts of the corrupt Azadian hierarchy to intimidate, bribe or kill him. At one crucial juncture, Gurgeh is on the verge of losing a game and being ejected from the tournament, so his AI drone escort decides to take him on a journey to new parts of Azad that Gurgeh has not already seen. This reveals that Azad is even more rotten and unjust than we previously thought, and stiffens Gurgeh’s resolve. He makes a tremendous comeback, and progresses to the final rounds of the tournament.

Whilst Banks uses vivid language when condemning Azad’s immorality, he has a light touch when describing the AI drone that brazenly manipulates Gurgeh. The implication is that psychological engineering is fine, when done by a clever machine to promote an outcome we should all agree with.

The reigning Emperor of Azad is Gurgeh’s opponent for the final match of the tournament, though the naughty cheating lying Azadian elite has already told the public that Gurgeh has lost. Hence the final game is merely an exhibition match, played to appease the Emperor’s vanity. In short, Gurgeh is doing a brilliant job of upsetting the Azadians by beating them at their own game, and the Azadians do a terrible job of just killing and/or throwing him out of a tournament which he is not eligible to win anyway. For all their ruthlessness, it is almost as if the Azadians want to be humiliated by this infidel! Banks can be a clever writer, but even a villain in a James Bond movie would roll his eyes at the conceit of the Azadians. Real tyrants persist by ruthlessly disposing of threats to their existence, not by welcoming them into their home and encouraging them to participate in lengthy pageants that also provide plenty of opportunity for intrigue.

Gurgeh’s progress in the tournament is not just representative of his personal accomplishments. Like Bobby Fischer defeating Russian grandmasters, or the sequence of victories by Russian grandmasters beforehand, Gurgeh supposedly wins because he is a product of his society, and demonstrates why that society is superior. Gurgeh did not merely choose to play in the tournament; the Minds that govern the Culture identified him as the Culture’s best player. His whole life has been dedicated to playing games because the Culture makes that lifestyle possible, and his abilities have been enhanced by the genetic modifications and educational riches bestowed on every citizen. And when Gurgeh temporarily loses his motivation, the AIs which run the Culture know which buttons to press in order to restore his will to win. Everything builds to one conclusion: the Culture is better than all others, and that is why it wins, whatever game is being played. This is psychological torture for the Azadians, and its ruler in particular.

For Banks, the tao of the Culture is psychologically dominant: others may pretend their society is better, but deep down they know the Culture would win any fair competition. This tao is arrogant, but not without precedent. Whilst religions often exhort their adherents to be humble, zealots may adopt the opposite attitude. Within the Culture, those who work for Contact are most likely to be zealots. Perhaps we should not be surprised if Banks identifies with Contact most of all.

Like other people of faith, Banks must struggle through his doubts before he enjoys his supreme vision. This is evident when describing the game between Gurgeh and the Emperor Nicosar, which begins badly for Gurgeh.

Gurgeh was immediately impressed Nicosar’s play. The Emperor didn’t stop rising in Gurgeh’s estimation; the more he studied [his] play the more he realised just how powerful and complete an opponent he was facing. He would need to be more than lucky to beat Nicosar; he would need to be somebody else. From the beginning he tried to concentrate on not being trounced rather than actually defeating the Emperor.

Gurgeh falls behind, and struggles to reconcile his performance with his self-belief.

He was missing something; some facet of the way Nicosar was playing was escaping him. He knew it, he was certain, but he couldn’t work out what that facet was. He had a nagging suspicion it was something very simple, however complex its articulation on the boards might be… An aspect of his play seemed to have disappeared…

But then, Gurgeh is manipulated by his drone companion again. Gurgeh had taken to speaking and thinking in the Azadian tongue. The drone forces him to use the Culture’s language instead. The superiority of the Culture’s tao is manifest even in the words it uses – which is also an important belief for many progressives. Forcing Gurgeh to speak the correct language is the key to his reaching his full potential…

After initially finding it rather needlessly complex, Gurgeh enjoyed hearing the language again, and discovered some pleasure in speaking it…

He had his best night’s sleep since the day of the hunt, and woke feeling, for no good reason he could think of, that there might yet be a chance of turning the game around.

Choosing the right words means thinking the right thoughts, and that leads to enlightenment.

It took Gurgeh most of the morning’s play to gradually work out what Nicosar was up to. When, eventually, he did, it took his breath away.

The Emperor had set out to beat not just Gurgeh, but the whole Culture. There was no way to describe his use of pieces, territory and cards; he had set up his whole side of the game as an Empire, the very image of Azad.

Another revelation struck Gurgeh with a force almost as great; one reading – perhaps the best – of the way he’d always played was that he played as the Culture. He’d habitually set up something like the society itself when he constructed his positions and deployed his pieces; a net, a grid of forces and relationships, without any obvious hierarchy or entrenched leadership, and initially quite profoundly peaceful.

The absurdity of Banks’ metaphor should be obvious to anyone who does not share Banks’ beliefs. Gurgeh is the game-player, the single decision-maker in his ‘society’. In the same way that Banks is the sole author of this work, it is nonsense to suggest that Gurgeh’s forces have no hierarchy or leadership. Banks merely plays the same trick that he always plays: focusing on the supposed ‘freedom’ of the individual pieces so we ignore the elite authority that moves them around.

However, if we ignore this serious fault with Banks’ thinking, we can see how the Culture possesses a ‘tao’. The Culture’s freedom leads to a way of playing every game, approaching every problem, solving every puzzle, though this may only become evident with a game and a player as sophisticated as Azad and Gurgeh. And the Culture’s way is inherently superior to all other ways.

Every other player he’d competed against had unwittingly tried to adjust to this novel style in its own terms, and comprehensively failed. Nicosar was trying no such thing. He’d gone the other way, and made the board his Empire, complete and exact in every structural detail to the limits of definition the game’s scale imposed.

Note that Azadian society is competitive, whilst the Culture is not. But Banks does not entertain the possibility that a competitive society is more likely to evolve varied and winning strategies than one where there is little incentive to compete. For Banks, the Culture just is better, and there is no need to explain how it came to be better, or why no better alternatives will ever arise. In that sense, the way Banks describes the inevitable victory of the Culture is just like the way Marx described the inevitable victory of communism. Again, I dislike this tao, but I have to accept that Banks has an unshakeable belief in the ‘way’ of the Culture.

Because Gurgeh has rediscovered the tao of the Culture, he starts to make a comeback.

He gradually remodelled his whole game-plan to reflect the ethos of the Culture militant, trashing and abandoning whole areas of the board where the switch would not work, pulling back and regrouping and restructuring where it would; sacrificing where necessary, razing and scorching the ground where he had to. He didn’t try to mimic Nicosar’s crude but devastating attack-escape, return-invade strategy, but made his positions and his pieces in the image of a power that could eventually cope with such bludgeoning, if not now, then later, when it was ready.

And so, even the playing of a game becomes subject to destiny. The Culture may appear to be losing, but so long as it remains true to its tao, it will prevail!

Having reached enlightenment, Gurgeh loses his identity and becomes an avatar for natural and divine forces.

Gurgeh was overcome by the sensation that he was like a wire with some terrible energy streaming through him; he was a great cloud poised to strike lightning over the board, a colossal wave tearing across the ocean towards the sleeping shore, a great pulse of molten energy from a planetary heart; a god with the power to destroy and create at will.

The breaks and the times when he slept were irrelevant; just the intervals between the real life of the board and the game. He functioned, talking to the drone or the ship or other people, eating and sleeping and walking around… but it was all nothing; irrelevant. Everything outside was just a setting and a background for the game.

Banks becomes explicit about the game being a form of communication, between the tao of the Azadian Empire and the tao of the Culture, or perhaps within the dualism of a universal tao.

He watched the rival forces surge and tide across the great board, and they spoke a strange language, sang a strange song that was at once a perfect set of harmonies and a battle to control the writing of the themes. What he saw in front of him was like a single huge organism; the pieces seemed to move as though with a will that was neither his nor the Emperor’s, but something dictated finally by the game itself, an ultimate expression of its essence.

Gurgeh is in rapture, partly as a result of continuously using intelligence-enhancing drugs that help him to play. The game-player becomes so divorced from his physical body that his drone escort has to monitor his bladder and tell him when to pee. The drone is concerned about Gurgeh’s wellbeing; if it had the choice, “it would have stopped the man playing there and then.” But the drone which has repeatedly manipulated Gurgeh is not free to do that, because “it had its orders.” Once again, Banks allows the facade of anarchy to slip, revealing the tao of the Culture depends on a hierarchy, even if discussing that hierarchy is taboo. Whilst the drone continues to keep Gurgeh functional, the game-player has been absorbed by the game, losing all sense of himself.

Breaks, days, evenings, conversations, meals; they came and went in another dimension; a monochrome thing, a flat, grainy image. He was somewhere else entirely. Another dimension, another image. His skull was a blister with a board inside it, his outside self just another piece to be shuffled here and there.

But as fulfilling as it is, the rapture must end, and the game must have a victor. As he has been sublimated into the tao, Gurgeh sees the inevitable outcome before anyone else.

Over over over. His – their – beautiful game over; dead. What had he done? He put his clenched hands over his mouth. Nicosar, you fool! The Emperor had fallen for it, taken the bait, entered the run and followed it to be torn apart near the high stand, storms of splinters before the fire.

Empires had fallen to barbarians before, and no doubt would again. Gurgeh knew all this from his childhood. Culture children were taught such things. The barbarians invade, and are taken over. Not always; some empires dissolve and cease, but many absorb; many take the barbarians in and end up conquering them. They make them live like the people they set out to take over. The architecture of the system channels them, beguiles them, seduces and transforms them, demanding from them what they could not before have given but slowly grow to offer. The empire survives, the barbarians survive, but the empire is no more and the barbarians are nowhere to be found.

The Culture had become the Empire, the Empire the barbarians. Nicosar looked triumphant, pieces everywhere, adapting and taking and changing and moving in for the kill. But it would be their own death-charge; they could not survive as they were; wasn’t that obvious? They would become Gurgeh’s or neutrals, their rebirth his to deliver. Over.

As the game proceeds towards the victory of Gurgeh and the Culture, the game-player feels empathy for Emperor Nicosar. However, Banks has little pity for those who are vanquished, and he restates the supremacy of the Culture whilst portraying its opponent as a cartoonish villain. On the eve of Gurgeh’s victory, Nicosar meets his opponent privately:

The Emperor was silent for a few moments. “You must be very proud of your Culture.”

He pronounced the last word with a distaste Gurgeh might have found comical if it hadn’t been so obviously sincere.

“Pride?” he said. “I don’t know. I didn’t make it; I just happened to be born into it, I-”

“Don’t be simple, Gurgeh. I mean the pride of being part of something. The pride of representing your people. Are you going to tell me you don’t feel that?”

“I… some, perhaps yes… but I’m not here as a champion, Nicosar. I’m not representing anything except myself. I’m here to play the game, that’s all.”

At this point, I wonder if Banks is being willfully obtuse when he puts these words into Gurgeh’s mouth. A man who spends his whole life perfecting his skill at playing games, who craves the pleasure of victory and says he would like to play for higher stakes, who consciously meditates on the tao of his Culture and plays in a way that represents its ethos, claims that the victory represents nothing. This sounds to me like the self-deception of an ideologue who refuses to acknowledge his own ideology. Meanwhile, Nicosar is reduced to playing the role of comic-book villain, with religious overtones.

“You disgust me… Your blind, insipid morality can’t even account for your own success here, and you treat this battle-game like some filthy dance. It is there to be fought and struggled against, and you’ve attempted to seduce it. You’ve perverted it; replaced our holy witnessing with your own foul pornography…”

Emperor Nicosar is right: the game is not just a game played by two players. The Emperor is devastated because the Culture’s tao is about to prevail. His belief-system has been fatally undermined, and so has the faith of every member of Azad’s ruling elite who has watched this final game. Even if Gurgeh vacillates, Nicosar acknowledges the tao of the Culture. For me, this is enough confirmation that the Culture has a tao; it is akin to a moment of religious conversion. Though Nicosar rejects the values of the Culture, he can no longer dismiss their potency.

Gurgeh will win because he has followed the Culture’s tao, but the uplifting nature of the Culture’s tao has always been implicit. Its citizens are well-fed and safe, its rivals are demons, but nobody so far has explicitly argued for the moral superiority of the Culture’s tao. So Banks finally uses Gurgeh as a mouthpiece for why the Culture’s tao is stronger. As communists often do, Banks constructs an argument for the Culture that relies heavily on criticism of the alternative offered.

Gurgeh… felt dizzy, head swimming. “That may be how you see it, Nicosar… I don’t think you’re being entirely fair to-”

“Fair?” the Emperor shouted, coming to stand over Gurgeh… “Why does anything have to be fair? Is life fair?” He reached down and took Gurgeh by the hair, shaking his head. “Is it? Is it?”

… Gurgeh cleared his throat. “No, life is not fair. Not intrinsically… It’s something we can try to make it, though,” Gurgeh continued. “A goal we can aim for. You can choose to do so, or not. We have. I’m sorry you find us so repulsive for that.”

At last Banks shows the cards he has been holding all along; being rather weak, he was wise not to play them sooner. The tao of the Culture is best expressed by the vague concept of fairness. Like many arguments for fairness, it is best not to examine what this entails, in case the unanimity of support for fairness is fractured by thousands of disagreements about what is fair in actual practice. However, though fairness is a vague concept, it is essentially uplifting. All other things equal, nobody prefers an unfair outcome to a fair one.

And for a man who writes a lot of words, Banks offers an ingenious excuse for why he will not examine the concept of fairness more closely:

Were they to argue metaphysics, here, now, with the imperfect tool of language, when they’d spent the last ten days devising the most perfect image of their competing philosophies they were capable of expressing, probably in any form?

But though he has wriggled out of the need to express why the Culture’s tao is superior, Banks cannot resist one brief (and seemingly reluctant) victory speech.

What, anyway, was he to say? That intelligence could surpass and excel the blind force of evolution, with its emphasis on mutation, struggle and death? That conscious cooperation was more efficient than feral competition?

And so we have the tao of the Culture, which unsurprisingly reflects Banks’ belief that central, common, benevolent, rational planning will always yield better results than the diversity promoted by competition. It even yields better results when playing competitive games!

A more sensible Emperor might have simply told Gurgeh and the Culture to leave, and then returned to ruling his Empire. However, the acknowledgement of the Culture’s tao is too much for the Emperor to bear, so he goes bonkers and kills everybody, thus hastening the demise of the Azadian Empire. The only survivors are Gurgeh and the drone that escorts him, thanks to their superior technology. At this point, it is revealed how much the drone and other AIs were manipulating Gurgeh and the Azadian elite, with the goal of encouraging the self-decapitation of the Azadian Empire.

“You’ve been used, Jernau Gurgeh,” the drone said matter-of-factly. “The truth is, you were playing for the Culture, and Nicosar was playing for the Empire. I personally told the Emperor the night before the start of the last match that you really were our champion; if you won, we were coming in; we’d smash the Empire and impose our own order. If he won, we’d keep out for as long as he was Emperor… That’s why Nicosar did all he did. He wasn’t just a sore loser; he’d lost his Empire. He had nothing else to live for, so why not go in a blaze of glory?”

“Was all that true?” Gurgeh asked. “Would we really have taken over?”

“I have no idea. Not in my brief; no need to know. It doesn’t matter; he believed it was true.”

… “You really thought I’d win?” he asked the drone. “Against Nicosar? You thought that, even before I got here?”

… “As soon as you showed any interest in leaving. [We’ve] been looking for somebody like you for quite a while. The Empire’s been ripe to fall for decades; it need a big push, but it could always go… Everything worked out a little more dramatically than we’d expected, I must admit, but it looks like all the analyses of your abilities and Nicosar’s weaknesses were just about right. My respect for those great Minds which use the likes of you and me like game-pieces increases all the time… All you needed was somebody to keep an eye on you and give you the occasional nudge in the right direction at the appropriate times.” The drone dipped briefly; a little bow. “Yours truly!”

And if that was not sufficient manipulation to make you question how much freedom is enjoyed by citizens of the Culture, Banks’ final revelation is that the drone which accompanied and manipulated Gurgeh is a disguised version of Mawhrin-Skel, the supposed outcast which first bullied and blackmailed Gurgeh into working for Contact.

So the Culture has a tao, but whether you consider it uplifting depends on your values. Its citizens have freedom, so long as they think and do the right things. If they are inclined to think and do otherwise, then the great intelligences who make all the important decisions will correct their thinking, by using deceit and blackmail if necessary. The Culture is transparent and honest, except to the extent that it is not, and it has no desire to conquer other territories, although they consider it a moral requirement to civilize their neighbors and absorb them into the Culture using the most efficient methods they can. Its people are cared for materially, but have no spiritual needs. The Minds who quietly govern the Culture only need extreme rationality to determine the difference between right and wrong. And if anybody offers an alternative point of view to theirs, then they will be defeated by the Culture’s superior technology and resources, which is proof that might equals right, and that being right makes you mighty.

I do not subscribe to these values, but I know some people do. Whether you consider the tao of the Culture to be uplifting depends on which direction you consider to be up. Banks loves his Culture, and is an apologist for every dirty track played in its name, but he dodges the greatest challenge to its tao. As useful as rational thought is, how could rationality ever construct a moral compass? Banks follows the lead of other atheist communists by maintaining blind faith in ‘rational’ values that cannot be derived rationally. The only way to avoid the moral ambiguities that trip up every attempt to ‘scientifically’ extrapolate from reason to morality, is to admit to a foundation of moral absolutes. Those absolute principles are like the rules of a game, not adopted by convention but because they describe the genuine Tao, and hence guide us towards a good and fulfilling life. Though I disagree with his conclusions, I admire the extent to which Iain Banks devoted his life to promulgating his beliefs. The challenge for any author wishing to depict a successful utopia with a strong moral dimension is to understand the extent of Banks’ accomplishment, and then to do more.

Be the first to comment