The sad truth is that some people want to exaggerate violence. Fear is a source of power. If you can frighten, anger, outrage and disturb people, you can manipulate them. The threat of violence is potent, whether real or imagined. Recently I blogged how one campaigner used a debunked statistic about violence to bolster her arguments for a change in British law… and perhaps also to draw attention to herself. It depresses me to see that over 200 people tweeted links to the offending article, because many of them dedicated their 140 characters to the misinformation it presented, in the mistaken belief they were raising awareness instead of spreading lies. Violence is an evil, and dishonesty is an evil. We get used to these evils; we find it hard to imagine a world free of them. I often write about information and misinformation, important numbers and public ignorance of them. Today I want to discuss numbers in the context of a major source of violence. I feel compelled to write about something I have long put off: an analysis of the chances you will kill yourself. These particular statistics about violence are never exaggerated, are often neglected. They tell us a story about our society, its priorities, and how they are wrong. I hope that once you know the facts, you will remember them, and that your priorities will change accordingly. If enough people know the facts, maybe our society’s priorities will change, and we might start to address the waste of human life caused by our indifference to self-inflicted violence.

Apologies for readers elsewhere, but I will begin with statistics drawn from the United Kingdom; I will briefly discuss statistics for other countries later on. Whilst suicide rates vary between countries, my chief conclusion holds true across borders.

For the purposes of crime statistics, homicide is murder, manslaughter or infanticide. The reporting periods differ slightly, but for the reporting year 2012-13, there were 551 homicides in England and Wales, 62 homicides in Scotland, 17 murders and 3 manslaughters in Northern Ireland. This gives a total of 633 homicides in the UK per annum, ignoring the differences in the reporting periods.

During the 2012 calendar year, the UK registered the suicide of 5981 people aged 15 and over.

633 homicides versus 5981 suicides. Do the math. Statistically speaking, a Brit is over 9 times more likely to kill themselves, than to suffer homicide.

In the run up to the next general election, politicians will frequently talk about murder, both specific ones and the statistics overall, in order to sway voters. They will insist that they are doing everything possible to tackle violence, or they will promise they will do even more than the other lot has already done. But they will not mention suicide nine times more frequently than they mention murder. They will not promise to dedicate nine times the level of resources to suicide. One of the reasons they will not talk about preventing suicide is because not enough voters ask them about it. Please keep this in mind, next time you hear a politician or activist, saying what needs to be done to reduce violence, or relaying a lurid story about how someone was murdered.

Why do we care so little about suicide? I have a theory relating to that, and it may be unpopular. But let me retreat to the data before I share it.

When the British public was asked their opinions for a wide-ranging survey about important numbers and social policy, the British public believed that 33% of crime involves violence or the threat of violence. The true figure is 24%. 51% believed that violent crime is rising, even though it has fallen significantly and repeatedly. Many people choose to believe society is more violent than it really is.

When you look at the data tables for that survey, there is an interesting split of attitudes according to gender. Women are more likely to overestimate violence than men. 8% of women felt that violent crime falls into the 41-50% band, compared to 5% of men. 7% of women, compared to 4% of men, felt it was in the 51-60% band, and so on. On average, women estimated that 36.4% of crime is violent; men estimated that 30.1% of crime is violent. Asked if it was true that violent crime is rising, 53% of women believed it to be true, compared to 48% of men.

This gender skew in perception cannot be explained by who suffers violence. The most recent relevant statistical analysis covers the year 2011/12. It stated that 62% of all violence is against men. That means that 3.8% of men are victims of some form of violent crime during the year, compared to 2.1% of women. 68% of homicide victims are men.

Another common perception is that young adults are most likely to suffer violence. Whilst young adults do suffer much more violence than older groups, children under 1 year of age are the most likely victims of homicide, at 21 homicides per million, compared to 15 homicides per million suffered by those aged 16 to 29.

There are some types of violence that women suffer more than men, especially sexual violence. 7.3% of women experience domestic abuse, and 51% of female homicide victims are killed by a partner or ex-partner. This contrasts with 5% of men suffering domestic abuse. When men are killed, it is most likely to be at the hands of a friend or acquaintance (39%). Rates of domestic violence are thankfully falling. By 2011/12, domestic violence was 74% lower than the peak value in 1993. However, it should be noted that there are many reasons to believe sexual violence continues to be underreported.

The conclusion I draw from this is that women are most likely to fear violence, but that men are most likely to suffer violence. This disparity may be exacerbated by biased media coverage. Feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez recently asserted the following.

Women murdered by men are often described by the media as tragic. There is a sense in that word of catastrophe, of horror, of something out of the ordinary. Something that could not have been prevented. Perhaps that word gives us a sense of comfort in the face of such brutality. This could not have been predicted, there is nothing we could have done. This is a freak accident.

Such words may comfort us, but they are dangerous, and our comfort comes at a cost of reckoning with a reality that we must face if we are serious about tackling the epidemic of domestic violence. And make no mistake: it is an epidemic… It is an epidemic to which we are so inured that the steady reports of abuse, of beatings, of assaults, of imprisonment, of death, barely register. They are not front-page news. After all, to put it bluntly, “man kills partnerâ€, is not news. It is the opposite of new. It is old. Tragically old.

I think the data tells us a very different picture. If there is an epidemic of violence against women, there is an even greater epidemic of violence against men. And if there is an epidemic of violence where people are killed by other people, there is a much greater epidemic of violence where people kill themselves. That is not to suggest that any violence is tolerable. But it does help to put emotive words like ‘epidemic’ into some kind of context. I am sure our society can do more to reduce the frequency of domestic violence, and the number of women murdered by men. Having said that, how do we now feel about society’s efforts to tackle the epidemic of suicide?

I will continue my unpopular theory on why we care little about suicide. Again, let me present some data first. The Samaritans reviewed and augmented the data on the 5981 suicides that occurred in 2012. Of the victims, 4507 were men. Men commit suicide at least three times more frequently than women. More men commit suicide than women in every age group, and in every part of the UK. Young men are most likely to kill themselves in Northern Ireland, thirtysomething men are most at risk in Wales, whilst middle-aged men represent the largest share of suicides in Scotland and England. Suicide rates have declined only slightly across the UK, except in Northern Ireland, which saw a sharp rise between 2004 and 2006, and has fluctuated since.

Keep the following in mind. If the rates remain steady – 51% of women are killed by male partners or ex-partners, women are the victim of 32% of homicides, and there are 633 homicides per year – then we can expect 103 women will die each year at the hands of male partners and ex-partners. That means British women are over 13 times more likely to kill themselves, than to be killed by a current or former partner. It also means that a typical British man is 44 times more likely to kill himself, than to kill a female partner. What does this say about our perception of ‘epidemics of violence’, and the moral panic surrounding them?

Just as violence against women may be underreported, there is also a problem of the underreporting of suicide. As the Samaritans put it:

It is commonly acknowledged by professionals in the field of suicide research that official statistics underestimate the ‘true’ number and rate of suicide. This is not only the case in the UK and ROI but in most (if not all) countries.

Please read the full Samaritans report for a complete understanding of why suicides are underreported. The report also highlights the problems of comparing suicide statistics between nations. That said, they compare suicide rates for the UK with those for the Republic of Ireland, and the numbers are not that different. The difference between the genders is similarly pronounced; Irish men are almost 5 times more likely to kill themselves than Irish women. However difficult it is to compare stats between countries, male suicides exceed female suicides in almost every country in the world. In the USA, the ratio of male suicides to female suicides is 3.5:1. In Lithuania, 5.1:1. In Sri Lanka, 3.8:1. In Germany, 3.3:1. In Turkmenistan, 3.9:1. In Zimbabwe, 2:1. In Venezuela, 4.4:1. And so on, and on, men are dying at their own hands, all round the world, in disproportionate numbers. If the situation was reversed, feminists and other well-intentioned people would be crying out for a remedy. But where is the current outcry, where is our anger?

And be in no doubt that this is a real epidemic. The World Health Organization says that over 800,000 people die of suicide each year. That is one death every 40 seconds. As a killer, suicide is comparable to the 1.24mn who die each year from road accidents, the 627,000 who die from malaria, and the 521,000 who die from breast cancer. Do we feel as strongly about strategies to prevent suicide as we do about seat belts and air bags in motor vehicles, mosquito nets for African children, or research into cancer treatment? If not, then why not? Is it because the victims of suicide somehow deserve their fate, because they made the choice to die? Is it because most of them are men, and we are far more interested in ‘fixing’ men when they hurt other people, than when they hurt themselves?

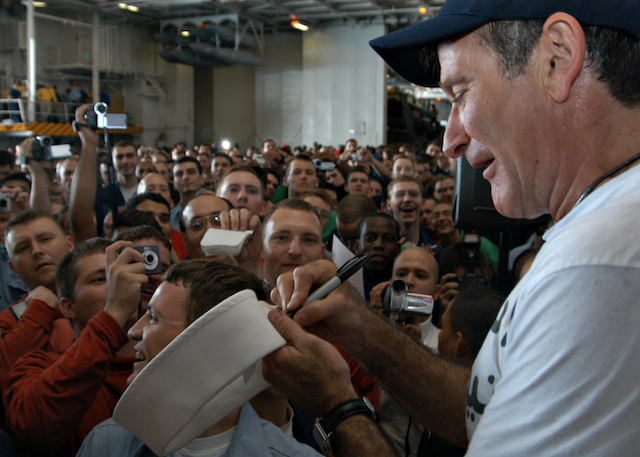

The pain of suicide is all around us. We see the victims again and again. Even the famous and successful are brought low by depression. Gary Speed. Kurt Cobain. Alexander McQueen. Tony Scott. Robin Williams. We mourn them, then move on, as if nothing needs to change. When a famous suicide hits the newspapers, the world endures another 2000 suicides that day, without further comment. And for every person who does commit suicide, there will be many more contemplating the act. Why are we blind to this pain around us? Why do we do so little about it? Is it that we do not care, or is the problem that nobody can turn this into a popular ‘campaign’ of the type that monopolizes headlines? It is easy to get people to sign a petition saying a woman’s face should be on a banknote, but much harder to reduce suicide prevention to a glib one-line demand for change. Or is the problem that we only care about violence when there is somebody to blame? Are we indifferent to suffering, if we choose not to imagine ourselves as a possible victim?

Our media presents suicide like each is an individual tragedy. I rather believe our society can do more to prevent suicide, and that there would be less suicide if we changed the priorities of our society. This would benefit both women and men, though statistically men would benefit more, because they currently suffer more. We should be doing plenty more. As the World Health Organization explains:

There is compelling evidence indicating that adequate prevention and treatment of depression and alcohol and substance abuse can reduce suicide rates, as well as follow-up contact with those who have attempted suicide.

And WHO tells us about the obstacles too…

Worldwide, the prevention of suicide has not been adequately addressed due to basically a lack of awareness of suicide as a major problem and the taboo in many societies to discuss openly about it. In fact, only a few countries have included prevention of suicide among their priorities…

It is clear that suicide prevention requires intervention also from outside the health sector and calls for an innovative, comprehensive multi-sectoral approach, including both health and non-health sectors, e.g. education, labour, police, justice, religion, law, politics, the media.

I admit that I started writing this article in an angry mood, not least because a feminist spread a lie about domestic violence being the largest cause of morbidity for women aged 19-44, even though it definitely is not. She did it to persuade people to support a change to UK law, and I was peeved at the thought that ‘awareness’ is not being raised in the ways it most desperately needs to be raised. But having reached this stage, having re-read all the terrible statistics about suicide, I feel a different kind of emotion. I want to learn from that feminist’s example. Some people are doing sterling work to address the epidemic of suicide. More of us must help them. We must campaign for change. People should be more aware of what can and should be done. For example, the charity CALM is taking an innovative approach to countering suicide in the UK, by finding new ways to reach out to vulnerable men. We need charities like CALM more than ever, because as they succinctly put it:

Suicide is now the single biggest cause of death in men aged 20 – 49 in England and Wales.

And that is the truth.

Supporting charity is a good thing, but we also need to become political. The next British general election is less than 300 days away. We should use this time to press politicians, of every party, to explain their response to the WHO’s call for ‘an innovative, comprehensive multi-sectoral approach’ to suicide prevention. The old political bullshit is not good enough. Effective strategies to counter suicide demand more than simplistic, standard policies that politicians parrot about the economy, healthcare, and welfare state. For the first time, the government has issued an annual report on the performance of cross-government strategies to prevent suicide in England. Voters must demand no less for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We should familiarize ourselves with the findings, popularize the work already done, share the lessons learned, and talk about the steps we still need to take. And then we must hound politicians to compete with each other, demanding they detail the solutions they would pursue, if put in power.

Suicide is an epidemic of violence, inflicted on ourselves by our ignorance, our apathy, our silence, and our sadness. If I was a feminist writing about domestic violence, you would automatically grasp the connections to the political sphere. I am a man, writing about self-inflicted violence, and saying this is a political issue. We must stop averting our eyes, stop treating every suicide like a stand-alone tragedy, and start being ferociously political about how society prevents suicide. I am frightened, angry, outraged and disturbed by how our society passively tolerates the ongoing waste of human life, taken from us every day by suicide. I hope that by reading this, I have passed those feelings on to you, and you will pass them on to others.

Be the first to comment